Problem-solving Technique: Integrated Assumption

Even though writing down the problem can help us solve it, it’s also a form of defining the problem. Thus, we will tend to define problems according to a nomenclature that we typically use. Since problems don’t care how we define them, our problem-solving approach problem will tend to be clunky and segregated rather than smooth and integrated.

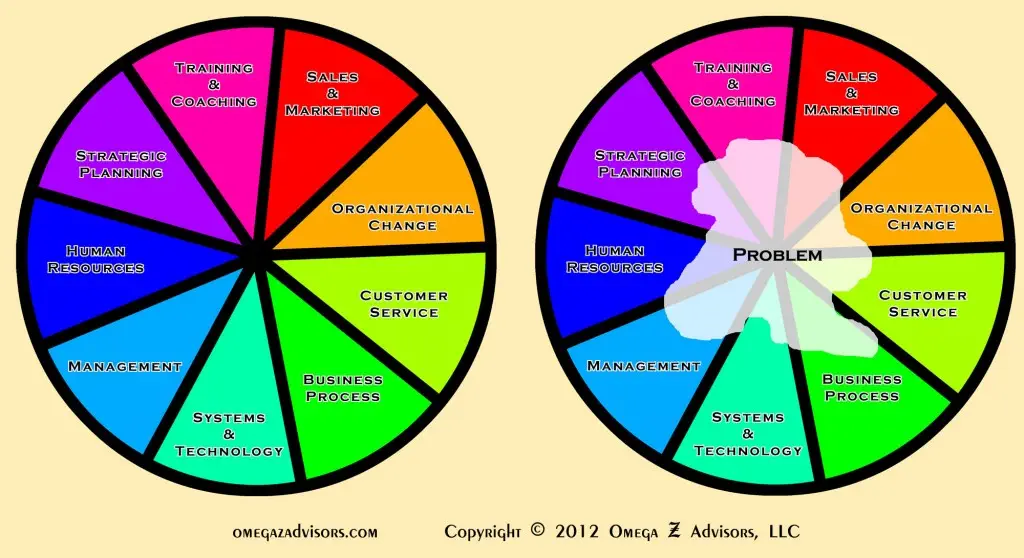

For example, below is a schematic. On the left is a typical functional perspective of business. On the right how a problem has no regard for those functional boundaries.

While obvious, we easily forget. For instance, if we define a problem as, “We need to generate more sales,” we will automatically tend to view it initially as a Sales & Marketing problem. In actuality though, many aspects such as pricing, delivery, servicing, management and technology could exist.

Therefore, in solving problems, it’s best that we assume the solution is an integrated rather than a segregated one. In other words, rather than ask something such as:

- Is this part of the problem?

- Does the problem affect this?

We should ask whether we can prove without a doubt that:

- This isn’t a part of the problem?

- The problem doesn’t affect this?

Thus, returning to the above example, rather than start from the premise that it’s a sales and marketing problem and then see if any other area is affected, start from the assumption it’s a business-wide, integrated problem and eliminate areas as we conclusively prove that they aren’t involved.

By assuming the problem is bigger and more integrated than we initially perceive it, we expand our field of potential solutions and success. Moreover, since we aren’t omniscient, it’s often better to assume the problem is more involved than it initially seems.

To me, the key for me and my advice to others is to keep the objective from including any possible solution. I don’t know if readers heard about the actual issue in a hotel renovation where, after reopening, complaints of slow elevators were numerous. That after there were few complaints before the renovation with nothing changed regarding elevator operation.

In using this with students, frequently the objective chosen was “wanting to improve the elevator speed.” If accomplished, that would presumably reduce complaints. BUT that objective includes but one possibility for the better objective: “reducing the number of guest complaints about slow elevators.” Not only does this objective Not include a possible solution (my point in these comments), remember no change was made to the elevators during renovation.

In the actual problem solving, the solution was adding mirrors and “things to do” listings beside the elevators. Complaints went away about slow elevators. Turns out that a decision was to “clean up” the hallways to make them sleeker. In doing so, there was nothing to occupy guests waiting for the elevators – except wondering when the elevator would arrive. The mirrors and listings were a cheap change that worked!!!

Kind of similar to your thinking, Mike: keep options open in setting the objective.

Thank you, John. I had not heard about this. This is definitely in line with the theme of this post. I also like it because the solution was to impact subjective aspects (how people felt while waiting) rather than objective ones (making the elevators move faster). I’m going to have to use this one.