Five Point Scales Misleading You On Predicting Consumer Behaviors?

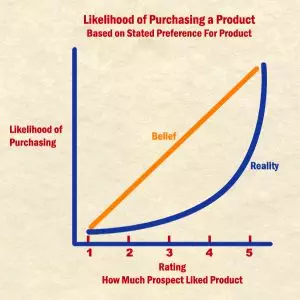

Figure 1: When it comes to finding the relationship between consumer likes and consumer purchases, five point scales lead us to believe there is a straight-line relationship. In reality, it’s not.

Five point scales show up everywhere. They often mislead people though. It’s especially true when people use them to make predictions. Predicting purchases from stated consumer preferences ratings are a prime example.

Using Five Point Scales to Gauge Preferences

For instance, how likely is someone to buy eggs? People often use five point scales here to assess how much the person likes eggs. A “1” might mean he doesn’t like them at all. A “5” might mean he loves them. It makes sense. The more one likes eggs the more likely she’ll buy them.

This then is how people typically try to predict purchases from stated preferences. The problem is that people are awful at doing what they think they will do. This skews the scale. It taints decisions.

The Misleading Differences Between Each Rating

As a start, look at the difference between ratings. This skewing means the difference between a “3” and a “4” is not the same as that between a “4” and a “5.” Yes, math says each is “1.” Yet, that difference of “1” does not mean the change in buying behavior is the same.

The story is this then. The jump in likelihood of a purchase from 4 to 5 is far, far greater than the jump from 3 to 4, from 2 to 3 or even from 1 to 2. Figure 1 shows how big that jump increases from number to number. Thus, whereas five point scales might lead people to think the jump between numbers is the same, they aren’t.

A Realistic Way to Look at Five Point Scales

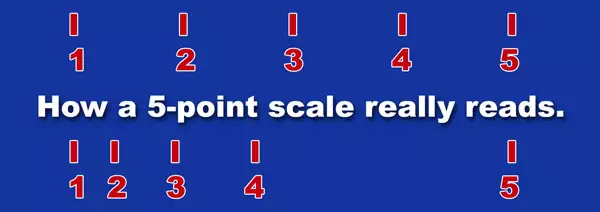

Figure 2: For predicting consumer purchases from preference ratings, it’s all about the fives. Even fours only give mediocre confidence in predictions.

In reality, “5’s” are in a league of their own. Only they hold any water when it comes to predicting purchases reliably. Thus, as Figure 2 shows, people should view five point scales differently in these instances.

Still, as a reminder this particular distortion of five point scales applies to situations in which one tries to predict purchases from stated consumer preferences for a product or service. This involves money. For instance, gauging interest to predict attendance at a free concert would skew the scale differently.

On the other hand, even with this caveat, decision makers need to be wary of five point scales and their cousins such as ten point scales. A difference of “1” might be mathematically right, but when it comes to people’s behaviors, 1 ≠ 1 on five point scales.

Note: Figure 1 is based on a figure in the article, “Linear Thinking in a Nonlinear World” by Bart de Langhe, Stefano Puntoni and Richard Larrick in the May/June 2017 issue of the Harvard Business Review